In December 2025, Mimeta’s reporting centred on the Middle East and North Africa, based on cases of artistic censorship and repression across Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Iran, Palestine/Israel and selected neighbouring contexts. Cases are identified by a mix of local researchers reporting in the Civsy database and AI search and retrieval from Internet sources. This more focused lens shows how, within this region, artistic life is increasingly shaped by a dense web of security agencies, religious institutions, professional bodies and informal pressure networks that together determine what can be seen, heard and performed.

READ the AI generated executive summary for 22 of the Memos published in Desember 2025 here.Artistic freedom across the Middle East and North Africa is being shaped by a dense web of state power, religious authority and informal pressure networks.

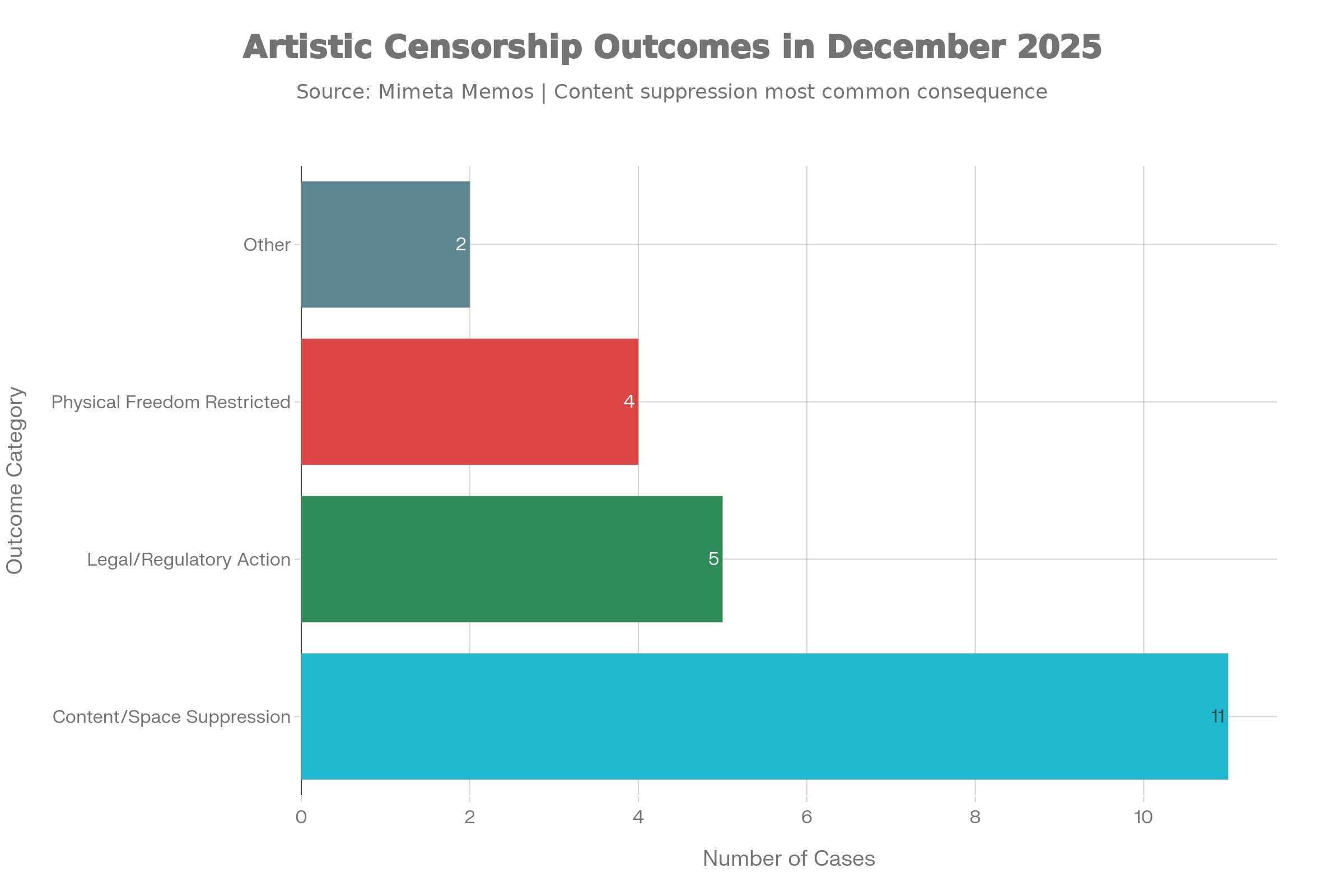

Mimeta’s December reporting highlights how artists face arrest, disappearance, cancelled events and invisible censorship, often without written bans or legal recourse. Women artists, minorities and those engaging with religion, identity or Palestine are among the most exposed.

Understanding these region-specific dynamics is essential to effectively support artistic freedom.

#ArtisticFreedom #Censorship #MENA #FreedomOfExpression #ArtsAndCulture #HumanRights #CulturalPolicy #ArtistsAtRisk

State power, para‑state enforcers in MENA

Within this regional sample, state actors remain the primary drivers of censorship, responsible for roughly two‑thirds of the December cases. Ministries, security services, courts, censorship boards and public universities intervene directly: Syrian and Iraqi authorities block novels and live comedy, Egypt’s syndicates and censors restrict musicians and films, and Iranian intelligence disappears a young Kurdish violinist after cross‑border collaboration.

At the same time, the region’s cultural field is heavily influenced by non‑state and para‑state actors who operate in the shadow of state power. Armed groups and militias in Syria and Iraq threaten fashion shows, close cafés and abduct performers; conservative religious movements in North Africa and the wider region launch campaigns against films and musicians; and online moral outrage helps push individual cases into courts or security channels. In many MENA contexts, these actors function as de facto cultural police, especially where formal institutions are weak, fragmented or focused on security priorities.

Morality, religion and security: regional master narratives

Because the December monitoring is MENA‑centred, it surfaces especially clearly how morality, religion and security shape artistic freedom in this region. More than half of the cases hinge on accusations of blasphemy, offence to religion or violations of “public morals”. Tunisian film Pomme d’amour is removed from a platform after being branded an intolerable offence to God; Iraqi performers and café workers are prosecuted or detained under public‑morals provisions; Syrian art students are threatened with academic punishment over nude act models; and moral scrutiny falls particularly hard on women and on gendered or sexual expression.

Security language is equally prominent. Iran’s enforced disappearance of Kurdish violinist Nima Mandoumi, following a concert in Armenia that included Israeli musicians, shows how cross‑border artistic collaboration is criminalised when it touches national red lines on Israel and Kurdish identity. The raid on Al‑Hakawati children’s theatre in East Jerusalem in November, justified by alleged links to the Palestinian Authority despite full licensing and international funding, illustrates how even heritage‑focused events can be reframed as security incidents. In Syria and Iraq, literary works are blocked or “corrected” on the grounds that they distort or destabilise official conflict narratives.

What happens to artists and spaces in the region

The December cases illustrate a spectrum of harms. On the most severe end, artists face arrest, imprisonment, abduction and enforced disappearance. Mandoumi’s incommunicado detention, digital performer Joanna Al Aseel’s prison sentence in Iraq, and the violent abduction of Syrian comedian Omar Khairy are stark reminders that creative work can still lead directly to loss of liberty and physical abuse.

More frequently, the immediate impact is the suppression of cultural works and venues. A Palestinian children’s performance in East Jerusalem is stopped mid‑show and the theatre cleared; Mosul’s Um Al‑Rabeain Café is closed after a video of employees dancing goes viral; a historic cinema in Damascus is reclaimed by religious authorities; and festivals, fashion events and film screenings across the region are cancelled under pressure from security officials, militias or religious constituencies. Books and films are kept away from audiences through a mix of formal bans, missing permits and quiet instructions to distributors and festival organisers.

These visible incidents are accompanied by longer‑term, less visible damage. Artists who become targets of campaigns, such as Deborah Sengl in Austria, whose case is included because of its resonance with MENA religious debates, lose future exhibitions and opportunities as institutions try to avoid controversy. Palestinian artists see their work shifted into closed or low‑profile formats in regional cultural centres and in European institutions that respond to the political climate around Palestine/Israel.

Informal and invisible censorship as deliberate strategy

Across the December MENA‑focused sample, one of the most striking patterns is the reliance on unwritten and informal tools. Syrian comedians have their shows in Hama cancelled through verbal messages that “every word is being scrutinised and reports are being filed,” even though official permits exist and no written ban is issued. Iraqi authors learn that their novels are no longer welcome at book fairs because of “verbal security instructions,” never tested in any court. Egyptian filmmakers with valid licences find their works confined to private jury screenings or delayed indefinitely through administrative hesitation and informal pressure.

These practices are not marginal anomalies; they are central to how censorship actually works in many MENA states. By keeping decisions off paper, authorities and institutions minimise avenues for legal challenge and maximise the chilling effect on artists and venues. Surveillance, online denunciation, “risk assessments” and moral campaigns together create an environment in which self‑censorship is often the rational choice for survival.

Regional focus, broader implications

Because the December monitoring intentionally zooms in on the Middle East and North Africa, its findings should not be read as a global distribution of artistic censorship but as a close‑up of a region where pressures are particularly intense and structurally embedded. Here, artistic freedom is constrained by the convergence of conflict, authoritarian governance, powerful religious establishments, economic precarity and the legacy of occupation. Cultural events can be treated as security threats; religious institutions wield formal and informal veto power; and armed groups or militias act as additional layers of enforcement.

At the same time, several December cases with a European or North American dimension, such as the Austrian campaign against religious art or the mass US school book bans, highlight how debates about religion, gender, sexuality and Palestine reverberate between MENA and other regions. The dynamics around Palestinian art in UK institutions and the policing of religious representation in Vienna, for example, mirror many of the social and moral pressures seen in Cairo, Baghdad or Tunis, even if the institutional settings differ.

Who is most exposed in this regional lens

Looking specifically through a MENA lens also clarifies whose artistic freedom is most at risk. Women artists and women workers in cultural spaces are repeatedly targeted when their visibility, clothing or movement is framed as a test of community morality, from café employees in Mosul to models in Basra and actresses linked to controversial films. Religious and ethnic minorities, including Kurds in Iran and Palestinians under occupation or in diaspora institutions, face additional scrutiny when their art touches on identity, memory and rights. Works that question religious authority, depict atheism, or explore queer or feminist perspectives on faith trigger some of the harshest campaigns and regulatory pushback.

These patterns show that, in the Middle East and North Africa, artistic censorship is not only about “sensitive content” in the abstract; it is also about controlling which bodies, identities and narratives may appear in public at all.

Using the December findings

By keeping the Middle East and North Africa at the centre of the December report, Mimeta is not suggesting that artistic censorship is uniquely regional but rather recognising that in this part of the world, the architecture of control is especially dense, and that supporting artistic freedom there requires sustained, region‑specific attention.

Artistic freedom under pressure beyond MENA

The December material also contained a small but important set of cases outside the Middle East and North Africa, showing that artistic freedom is being squeezed through institutional and social mechanisms in established democracies as well. While December’s monitoring mainly focused on the Middle East and North Africa, several cases from Europe, South Asia and North America underline that artistic censorship is not confined to authoritarian or conflict‑affected states. These incidents revolve less around open security crackdowns and more around institutional governance, moral campaigns and educational control.

Austria: Religious campaigns against contemporary art

In Vienna, a major exhibition at Künstlerhaus presenting critical, feminist and queer reinterpretations of Christian imagery triggered a coordinated campaign by the conservative Catholic group TFP and allied organisations. Through petitions and public “prayer of atonement” actions, they demanded closure of the show and singled out particular works and artists as blasphemous, including pieces reimagining the Virgin Mary and other sacred symbols.

Although the exhibition remained open, the pressure had real consequences: artist Deborah Sengl received abusive messages and saw at least one planned institutional exhibition cancelled, illustrating how organised religious‑political mobilisation can function as de facto censorship even without formal bans.

United States: Mass school book bans

In the United States, December’s overview highlighted the scale of school‑based censorship, with 22,810 book bans across 45 states over one year, heavily targeting titles that address race, gender, sexuality and LGBTQ+ lives. These removals are typically justified through language about protecting children from “inappropriate” content, implemented via school boards, parent complaints and state‑level policies rather than criminal law.

The result is a vast, decentralised form of cultural control in which young people’s access to literature and ideas is reshaped by political and moral campaigns that rarely name themselves as censorship.

India and international festivals: Films blocked by procedure

The material also pointed to film censorship operating through festival procedures rather than classic bans. In India, 19 films slated for the International Film Festival of Kerala were denied the required exemptions, without transparent public justification. By withholding administrative approvals, authorities effectively kept the films off the screen while avoiding explicit prohibitions, a pattern that mirrors broader trends where “exemption”, “classification” and “technical” decisions become tools of suppression.

United Kingdom: Governance tools limiting Palestinian art

In the UK, trustees and senior leadership in arts organisations were described as using “risk”, “reputation” and funding concerns to limit or reshape Palestinian art and programming. Instead of bans, institutions quietly moved events into closed formats, scaled them down, or declined proposals outright, citing governance responsibilities and external pressures. This approach shows how, even in longstanding democracies, institutional structures can be mobilised to narrow space for politically sensitive art, particularly where Palestine/Israel is concerned.